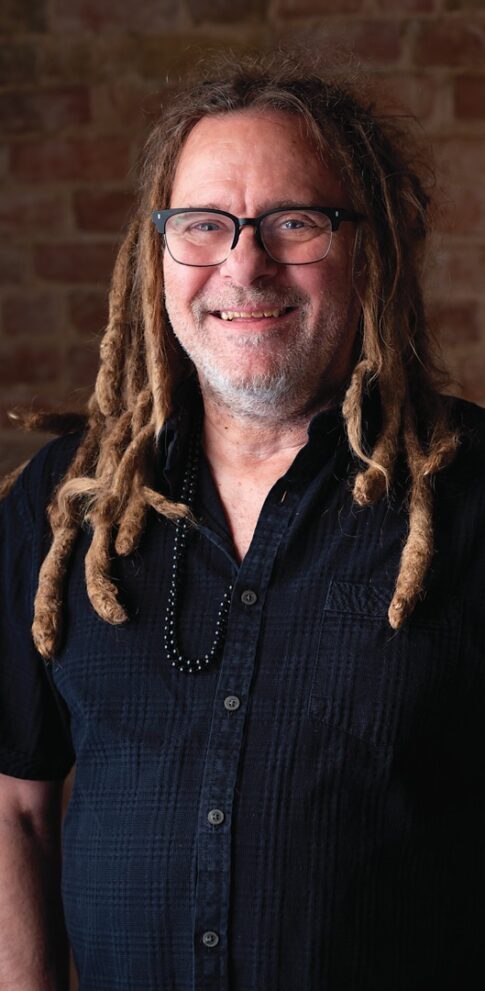

By Taylor Adams Cogan

Today, you can find Jeffrey Liles at concerts that fill the Kessler Theater and Longhorn Ballroom with music and inspired fans. As the artistic director of each, he’s booking the entertainment that people look forward to. While he’s working at venues with established names and reliable followings, Jeffrey got his start decades before on the other side of town, bringing local bands to an unassuming warehouse.

In 1985, Jeffrey was the youngest in a band called Group Six, playing some Dallas punk rock clubs in the city. He had time on his hands while the older band members went to day jobs, so he took it upon himself to hustle for gigs.

“One day, I went into an art gallery at 2808 Commerce, and I noticed they were letting bands play at art openings,” he says. “I met the owner, Russell Hobbs. He didn’t even listen to our tape or anything, and said, ‘We have an art opening in three weeks, and you can play that.’”

The timing was bad for the band: the rest of the group decided to break up. But it wouldn’t be the end for Jeffrey. When he went to Russell, saying they could no longer play, the Theater Gallery owner offered the musician a place to stay and a gig getting bands to play in the warehouse.

“I moved into the building, and there were about six or seven people living there at the time,” he says. “They were kind of hippies who had various interests in art. They had built these lofts out of plywood inside the building, and I moved in – literally moved my bed onto the stage inside this place – and slept on the stage the first couple of weeks I was staying there.”

This was the mid-1980s in Deep Ellum. No one paid a mind to people living in a 14,000-square-foot building far from residential zoning. The only speck of neon in the quiet neighborhood was a small “TG” outside the Theater Gallery. And booking a band took considerably more effort than today’s work.

“If you wanted to book a band, you had to go to the band’s show somewhere else, wait for the end of the show, meet them, get their contact information, and get them interested in coming to play,” he says. “At the time, there weren’t a lot of groups playing original music. They were mostly playing cover songs, and that was that. But here’s the catch – there were these younger bands playing their own original music situated all over town, in the different suburban neighborhoods.”

He found high schoolers making music in Carrollton, Highland Park, North Dallas, and more – all of them eager to have their music heard. He’d book one of these bands at Theater Gallery, and they’d bring hundreds of friends from their neighborhood.

“All of these kids came together to create a music community in this warehouse,” he says. “These kids who lived out in the suburbs, like Three On a Hill from Carrollton, The Buck Pets from Plano, Shallow Reign from Richardson, New Bohemians from East Dallas, etc…. And the Theater Gallery became this place where they would escape their own suburban neighborhood, and it was their secret.”

Part of the reason for that was the deal at the door: $5 to get in, then a night of free beer. This was just before the legal drinking age was bumped to 21, and Hobbs didn’t have a license to sell.

“It was like a keg party every weekend,” he says.

But music was happening again in Deep Ellum. While North Texas blues music flowed through these streets just after its founding, it had been decades since people started seeing it as a destination for live music. And this was the resurgence.

As it grew, Mark Lee and Danny Eaton reached out to Jeffrey to see if their concert promotions company, 462, could help book emerging national touring acts at the Theater Gallery. Here’s where and when more notable band names would play their first shows in Dallas, including Jane’s Addiction, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Husker Du, and the Flaming Lips.

“It kick-started an emerging alt-rock scene in the ‘80s,” Jeffrey says.

From there, Russell would open Prophet Bar across the street, targeting a more adult crowd, and booking residencies so people could reliably see the same musicians week to week. Meanwhile, Club Dada would open on Elm Street, which offered a good opportunity for Jeffrey to move on. And down the road, the Longhorn Ballroom was looking to him to bring in acts that would attract younger crowds.

“A lot of these bands that played Theater Gallery were getting bigger and started to need larger venues, so I booked them at Longhorn in conjunction with 462. I developed a sturdy relationship with them, and we ran the same playbook as Theater Gallery,” he says.

As for Club Dada, it carried its name because of the performance art group called Victor Dada. The focus initially wasn’t live music but on their improv and sketch comedy. The only thing was, the Victor Dada shows wouldn’t bring in the crowds that live music did.

“At the same time, the New Bohemians from the arts magnet high school was blowing up, and the backyard at Club Dada became their base, playing once every three weeks and bringing 600 to 700 people at a time,” he says. Denton performers Ten Hands, Sara Hickman, and Brave Combo also drew huge crowds on weekends. “These were the artists who drove the traffic to Club Dada and made it sustainable.”

And the bands started to get a taste of playing for real audiences.

“Most of the bands playing at Theater Gallery were rough around the edges, grunge bands, definitely a part of the weird alternative – I mean that in a good way,” he says. “Dada acts were a little more polished, MTV was still a thing at the time, and they paid more attention to what they wore; they were trying for something else other than what the Theater Gallery offered.”

At that time, there was a building on Elm Street that Jeffrey “lusted after.”

“It didn’t used to have a big front; it had big glass windows, and I would go over there and just stare into the windows. It had a descending wooden staircase that came down from the balcony into the middle of the building; it looked like an old, empty ballroom from a different era, and it had these pillars in the middle of the room that looked like tree trunks. The owner of the property left a single work light on all the time, so there was just enough light for you to peer into the building and imagine the possibilities. For a year or two, I would go over there and just stare at the interior, and imagine what it could be,” he says.

He would learn from band manager Jessica Clarke that a man named Brian Davis had rented the building and planned to turn it into a seafood restaurant.

“Jessica and I went and met with him, and we somehow managed to talk him into making a live music venue instead of a seafood place,” Jeffrey says.

He would book yet another iconic venue for its first three years after its opening in 1990.

“It was right when alternative rock really started to blow up, so we were in the right place at the right time. That’s how we were able to get Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Pearl Jam,” he says. “It was the first place in Dallas where a lot of those bands played.”

In 1994, Jeffrey would make his way to Los Angeles, pursuing his own music career. But now, he’s back to bringing live music to stages at the Kessler and Longhorn Ballroom. He still makes his way to Deep Ellum, eating at AllGood Cafe and St. Pete’s, catching up with his good friend Frank Campagna at Kettle Art Gallery, or going to shows at Three Links, Deep Ellum Art Company, and the Bomb Factory.

What drives him now is preservation – making sure the spirit that built Deep Ellum continues to have room to thrive.

It’s a lesson Liles learned sleeping on a stage inside a dark warehouse, when Theater Gallery’s neon glow stood alone on Commerce Street. Today, Deep Ellum lights up night after night, and that early experience still shapes how he thinks about live music, even beyond the neighborhood: scenes grow because people take risks, open doors, and give artists space to find their audience.